"Silent All These Years," Part One

Finding a safe place to over-share

(Part two will address the over-sharer’s gift for holding space for big feelings).

Recently, I was scrolling through Instagram when I saw an ad for an AI journal. The caption was something like, “Fuck oversharing on social media,” as it encouraged “over-sharers” to trauma dump to ChatGPT instead.

Another advertisement started out by saying, “This will hurt, but are you ready? The reason you talk so much and overshare is because you didn’t feel heard as a child.”

This one in particular resonated with me.

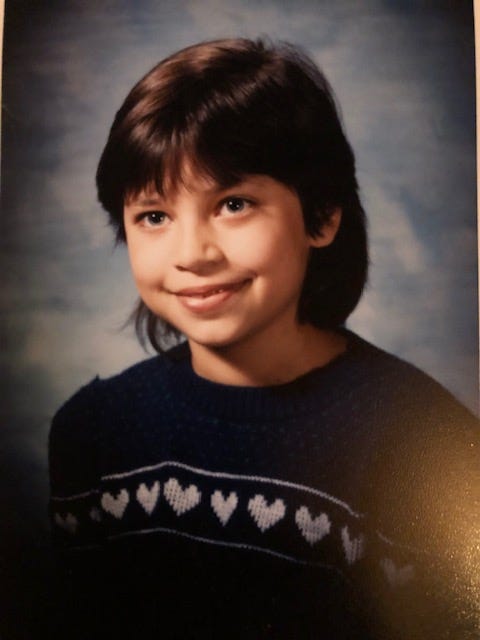

As a child, it wasn’t only that I didn’t feel heard, but there were times I literally couldn’t speak. Whether it was at school or at church, I felt a dizzying sensation when anyone put me on the spot, or expected me to verbally engage. My throat went dry, and I felt a tightening in my vocal chords that locked any speech. I would sometimes stand behind my mother, tightly gripping her polyester skirts, hoping that if I looked down at my shoes long enough, I would somehow disappear.

I remember being around nine or ten years old and visiting my aunt and overhearing her friend tell her, “Algo le pasa a esa niña,” translated: “something is wrong with that little girl.”

This wasn’t the first time I heard this as a child either. A doctor told my parents the same thing and urged them to take me to a child psychiatrist immediately, which led to my fanatically religious father calling and threatening him.

At school, I was often marked as absent, especially in middle and high school due to barely getting a “here” out of my mouth when teachers called my name. After roll call, I walked sheepishly up to the teacher to let them know I was in fact present. “Oh, I didn’t hear you.”

This inability to speak up in public spaces outside my family home, had consequences, often humiliating ones.

At the kindergarten I attended they took the doors off of all of the stalls. There were designated times to use the bathroom and that meant an entire class of girls entering the restroom at once. This felt impossible to me. It felt unsafe and embarrassing. I couldn't speak, and if I could, I couldn’t make my voice loud enough to be heard. I held it in for as long as I could, but by the time I mustered up the courage to approach my teacher, I had already pissed my pants. A little boy who saw the whole thing teased me about it all the way through high school.

The same thing happened in the third grade. I was terrified to ask the teacher to use the restroom before I was given the task to pass out homework sheets at the end of the day. Halfway through, with my bladder ready to explode, I quietly approached the teacher and asked if I could use the restroom. She said no, reminding me that it would be time to go home in just a few minutes. The moment class was dismissed I ran to the pick-up area towards my father’s truck, feeling my bladder relieve itself on the way. I sat in my father’s truck with my dark washed jeans camoflauging my urine soaked pants. My father had to run a few errands on the way home. I was too scared to tell him what had happened, so instead I offered to stay in his truck, alone with the stench and the humiliation.

At home with my sisters and my mother I couldn’t stop talking. But as I got older, this only applied to certain subjects. My thoughts were strange and esoteric. I wrote poems questioning the religion (cult) I was born into. I wrote about abuse, the frightening observations I had made of the adult world, and the feeling of not being at home in my skin or even on this planet. I remember showing them to my mother, hoping for something, I didn’t quite know what. Did I expect her to show interest, concern? Did I need validation? Was I seeking attention? It didn’t matter because my mother’s response was, “I think you should burn them.”

I ended up tossing a sixty-page novel I wrote in the sixth grade, a novella I wrote in the eighth grade and an entire poetry manuscript I wrote in the 9th grade into our garbage can.

I retreated back into my silence.

Around that time, Tori Amos released her breakthrough album Little Earthquakes. Like so many teens at that time, I joined music subscriptions like BMG, and Columbia House. My first order was the soundtrack to Twin Peaks and “Little Earthquakes”. I listened to these cassette tapes so much that I wore them out and eventually had to order new copies. The world and music of Twin Peaks, “a place both wonderful and strange” felt like home to a girl like me, a girl who had “something wrong” with her. But Little Earthquakes, especially the song “Silent All These Years,” felt like a prayer, like Tori had telepathically undone my most private and dangerous thoughts.

'Cause sometimes, I said sometimes

I hear my voice and it's been here

Silent all these

'Cause sometimes, I said sometimes

I hear my voice and it's been here

Silent all these

Years go by

Will I still, will I still be here waiting to understand?

Years go by

If I'm stripped, if I'm stripped of my beauty

And the clouds raining in my head

Years go by

Will I choke 'til finally there's nothing left?

One more casualty, you know we're too easy, easy, easy

Tori, another strange and unsettling girl, whose father was a pastor, was also born into a deeply religious family, like me. In her music, I recognized the pressure to be “good,” the prison of expected and mandatory silence. But even our silence wasn’t quite good enough:

In her song “Crucify”, Tori bellows:

Why do we crucify ourselves?

Every day, I crucify myself

and nothing I do is good enough for you

I crucify myself, oh every day

I crucify myself

My heart is sick of being

I said my heart is sick of being in chains

This is often how artists are born.

First, I couldn’t speak, and when I did it wasn’t loud enough. Then it was too loud and too much and too wrong, and I would hide in the corners again, writing what I couldn’t say, drawing and painting what I could see but not speak.

Decades later, I came across someone like me, someone whose voice stubbornly refused any and all prodding. I was working as an elementary school art teacher, when a fifth-grade girl was introduced to me as a “selective mute.” During class she was silent. I never forced her to speak, never put her on the spot. I recognized the panic, the impossibility of vocalization in her eyes. For the first time in my life I had a name for what was supposedly “wrong with me.” I had also been a selective mute.

When she visited me during lunch time, she spoke with abandon. She shared her wicked-sharp sense of humor, her jaw dropping talent for art, and bits and pieces of her home life.

It reminded me the bonds I formed with a few of my high school teachers. I often walked out into the track field during lunch time, as far away from peers as possible, eating my cold lunch and scribbling angsty poems and sad girl faces in my notebook. But when they were available, I hung out with my English teachers. I found a connection. I felt seen, I felt safe, and most of all I felt heard.

Then came the invention of social media and suddenly, the quiet girls had a place to (supposedly) safely share their thoughts, wave their freak flags, and find kindred spirits. Starting with MySpace and the discovery of blogging, I felt like I could finally claim a space for self-expression. I shared openly and unapologetically. I connected with hundreds of readers and writers, other quiet misfits, people who are often dubbed as over-sharers.

My safety bubble popped early on in my discovery when I found out I had lurkers, relatives who were offended and even appalled by my openness, as I wrote about everything from childhood abuse and trauma, to exposing the corruption and oppression of the cult I had been forced into since birth, and my opinions on God, religion, and politics. Cousins, aunts, and others gossiped and “told on me,” to my mother and siblings. I was twenty-fucking-eight years old. I shouldn’t have cared what they thought. But I’m also someone who is (sometimes overly) concerned with how I affect people. I felt ashamed and I retreated, only to come back stronger, and sometimes overly reactive with a “fuck you” attitude. Then, like always, came the shame and the quiet associated over-exposure, and fear of judgment.

This began a vicious cycle to which this day is still alive and unwell: share delete, share delete, share delete. Most recently I went through a major mental health crisis. I begged for help on social media, while I stayed in motel rooms, and ended up in emergency rooms for suicidal ideation. This is now referred to as being unhinged or even more popular and prevalent, “crashing out.”

In the beginning, I started posting videos documenting what I hoped would be a journey to healing in real time, to curate a space for connection and support. But I stopped when I realized that only two or three people out of 500+ followers, many of whom are family and IRL friends, liked or commented on my most vulnerable posts, while cute videos of my dogs and cat received tons of likes and comments. And again, I questioned myself. I felt embarrased. I regretted exposing my raw vulnerability. I archived all of my videos.

Then, even more recently I hit my first manic episode in years. At this point in my life, mania presents as irritability, troule sleeping, some impulsivity (much less than when I was younger) an inability to regulate my emotions and a constant need to express every single thought and feeling. It also brings brief bursts of confidence, of “let them,” infused bold and brazen Instagram and TikTok posts. But like always, I succumbed to fear and doubt and I deleted them just a day or two later.

I worried that I made followers uncomfortable, or that people would find my posts attention seeking, when what I really want is what I didn’t get as a child: to be heard, to be seen, and to find authentic connection. For someone to simply say, “I get it. I understand.”

I’m reminded of my favorite fellow bipolar baddie Carrie Fisher who admitted the following during an interview with Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air, “Oh, I think I do overshare, and I sometime marvel that I do it. But it’s sort of — in a way, it’s my way of trying to understand myself. I don’t know. I get it out of my head. It creates community when you talk about private things and you can find other people that have the same things. Otherwise, I don’t know — I felt very lonely with some of the issues that I had or history that I had. And when I shared about it, I found that others had it, too.”

“It creates community when you talk about private things and you can find other people that have the same things.

This is something I think about often when I head down a shame spiral. What some see as attention seeking, for me, is community seeking.

In regards to the ad I mentioned in the very beginning, the temptation to use an AI journal is tempting. It feels safer, emotionally, to share big feelings with an interactive journal rather than facing the often humiliating and uncomfortable silence after ripping your chest open, exposing the monster who mercilessly claws at your tender heart on social media. But I don’t want an echo chamber that tells me what I want to hear. I want that elusive, transcendent experience where the reverberations are messy, authentic and unabashedly human.

This is why I stopped (for the most part) sharing the rawest version of myself on social media. It’s the reason I joined Substack, in hopes of finding my people. After all, I’m living in a town that I only moved to in order to be closer to my now ex-partner. My community is completely non-existent. That silenced little girl inside of me gets restless and blue, disappointed in herself for feeling scared and going into hiding, for still searching for connection and validation.

It’s quiet here (Substack) for now. Writing without readers often feels incomplete and lonely. However, I’m a mere toddler, or an infant even, in my Substacking journey. I’m just beginning the search for my people: the misfits, the over-sharers, those kindred spirits who weren't seen or heard as children, the ones pained by small talk who struggle to find that ever so blurry line between vulnerability and oversharing.

So, if you’re out there, please introduce yourselves. I’ll listen.

Now I’ll leave you with my favorite Frida Kahlo quote:

“I used to think I was the strangest person in the world. But then I thought there are so many people in the world, there must be someone just like me... I hope that if you are out there and read this and know that, yes, it's true I'm here, and I'm just as strange as you.” Frida Kahlo

Tori Amos - Silent All These Years (Official Music Video) from the album 'Little Earthquakes' (1992)

Oh, Kristy. I hear you, I see you, and I understand. I see myself in your words so very much. I could have written so many of these lines myself, and after a lifetime of feeling painfully misunderstood, please don’t underestimate the healing properties of putting this work out there and helping people like me feel that spark of hope that comes from feeling understood. People like me need to read what you have to say.

I literally started a post of mine yesterday with something like ‘I have always felt that I was not normal’, and reading the end of your post helped remind me why I am here on substack. There must be more people like me, and you seem to be one of them. Thank you so much.