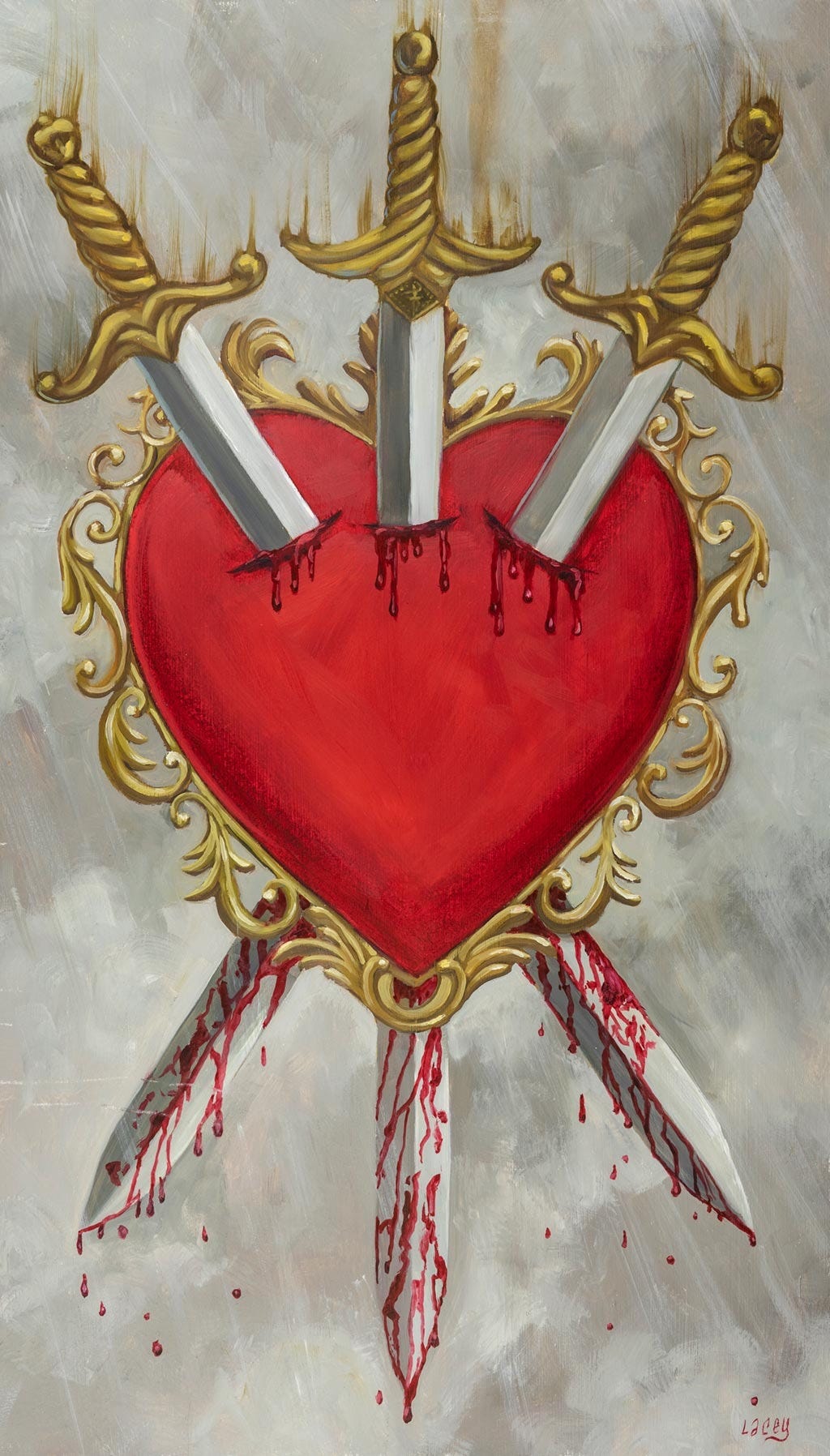

Reflection on the Three of Swords

The double edged sword of reclaiming our experiences while writing about how others have wounded us

The meaning of the Three of Swords according to the site Labrynthos is the following:

Upright meaning: heartbreak, separation, sadness, grief, sorrow, upset, loss, trauma, tears

Reverse: healing, forgiveness, recovery, reconciliation, repressing emotions

When I think about what I’m most compelled but terrified to write about, it always comes down to stories in which people, especially the people whom I love, might be portrayed unfavorably.

Anne Lamott famously wrote, “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”

So often our most relatable experiences involve sharing our uglies, our insecurities, our vanities, and our betrayals. And while I agree that we own everything that happens to us, I’m also aware of the overlap between what is mine and theirs and carefully consider which stories are mine to tell.

The authenticity of our storytelling relies upon our willingness to gut our lived experience, to write honestly about the impact—everything from trauma and woundedness, to inspiration and healing—our families, friends, partners, or stangers have had on us. We are our relationships and connections after all. It is impossible to reclaim and share our most vulnerable stories without involving all the key players.

For example, I have been teaching the book The Distance Between Us by Reyna Grande, one of my favorite and most esteemed writers for the past six years. In her memoir Grande writes about how her mother’s male centered abandonment leads to the children’s devastating neglect, while their father’s alcoholism and unprocessed childhood trauma manifests in violent physical abuse.

In addition, she also writes about her siblings whom she shares a close relationship without holding back, sharing how her beloved sister Mago once killed a litter of puppies, and how she once forced two little boys to eat “poop tacos.” This is how her sister coped with the anguish of losing both parents to El Otro Lado (the United States) and how she deals with the anger and resentment she feels for any vulnerable, tender creature who unlike her, has a soft lap to crawl on.

Students often comment on this and wonder how she went about getting permission from her siblings to write about some of their most shameful moments. They are horrifed by the details, but they are also forced to consider the unavoidable repurcussions of neglected and abused children, and how each child deals with their shared trauma in vastly different ways. In other words, these details are unavoidable. For Reyna to withold these examples of how their parents choices uniquely wounded each child would be avoiding layers of necessary truth.

Reyna’s story, one of childhood trauma and resilience, is absolutely a story worth telling, where each detail makes up the body of an essential and inspiring story: the guts, the heart, all the putrid and beautiful parts that give every page its skin and breath.

I’ve taught this book for six years for a reason. The majority of our students are first generation college students and often first generation Americans as well, just like Reyna and her siblings.

Students tell me it’s the first book they’ve ever read where they feel represented and seen. Tears are often shared during our seminars because Reyna’s voice is part of a cacophony of voices that have been silenced or ignored for in public education.

This brings me back to my internal conflict. When I look back on personal essays and short memoirs I’ve shared in the past twenty-five years, I sometimes cringe. I wonder if sharing some of my particular wounds is self-indulgent or necessary. I wonder if there are enough readers out there who would benefit from my story, or if I the damage I might cause to someone I love is worth it. It’s a tender balance that I continue to contemplate.

When I wrote the book Heretic: A Story Of Spiritual Liberation In Poems, I knew it would ruffle feathers. I knew it wouldn’t be for everyone. Not only that, it also painted some relatives and past friends—who are still members—in a not so flattering light. I prepared myself for, and expected a limited audience as I wrote about growing up in a cult. However, it wasn’t as niche as a subject as I had originally thought. What is wildly personal, is also deeply universal. And although my readership is small, the relatability of the experience isn’t. Whether someone has actually grown up in a religous cult or not, most people have spent phases of their lives under some kind of opressive , or, the unrealistic expectations of others. They know what it’s like to feel pressured to conform in order to find acceptance with a family, a group or community.

I don’t think that when I write about anyone in an unfiltered and truthful manner it’s because I think they deserve it, or out of some sort of righteous indignation. However, I recognize that for others, this is could be a totally valid reason.

I’m aware of the complexity of what one person or experience can encompass. Even Reyna wrote about brief and gentle moments she shared with her father. She also gave him credit for the life she lives now. If he hadn’t brought her over the border, if he hadn’t made education such a huge priority, she wouldn’t be where she is today. However, this didn’t change that he was violent and physically abusive. But it is a reminder that our monsters are also human.

Writing about relationships and interactions with others, whether harrowing or enlightening, has also been a catalyst for self-reflection, a guide to self-awareness and liability. For instance, my son, holds a very negative opinion of me, and while his perspective and recollection doesn’t often line up with my own, or others around at the time, I am prepared for a villain edit. I’m prepared to someday come across a post or essay about how much I traumatized him. I’m also prepared to admit some of the most awful truths about myself as a mother—bouts of serious mental illness that led self medicating with alcohol, a trail of failed relationships, times my temper and emotions got the best of me, and moments when I checked out and disassociated because being an impoverished divorced, single mother was too overhwhelming.

I hope he also remembers that even at my worst I was still attentive, encouraging, and loving. But I won’t bet on it. I too, tend to mostly remember the worst parts of my childhood, the moments which caused the deepest wounds.

The truth is that the experience of humanness is messy. It’s often gross, and mean, and cruel. We are frequently reckless with one another, careless with our floppy bodies and our delusions. Still, through our kinks and disfigured logics, we can also be adorable and relatable.

Every way in which we love and wound each other is part of our story. Everything great and garish connects us to our unmistakable essence.

All is fair in love and memory, I suppose.

What I agree to is to write about myself—at my sickest, and most selfish, my terribles and my wonderfuls—with as much radical honesty as I write about others.

I’ll also continue to ask myself which stories are worth telling. I’ll weigh which excavations will bring healing and inspiration to others, which ones might only serve to re-wound and re-traumatize myself or others.

Like the upright and reverse meanings of the Three of Swords—heartbreak and trauma vs. forgiveness and reconciliation—I have to ask myself which exposed details and portrayals in my writing will boomerang and set everything back, and which ones will propel my storytelling towards accountability, authenticity and connection.

Just getting around to reading this one and I really enjoyed how you braided together so many delicate topics. People toss around Anne’s words a lot but I still think it’s worth considering what to share and when. Like you said, I don’t want to make myself cringe later, but it happens!